Model summary

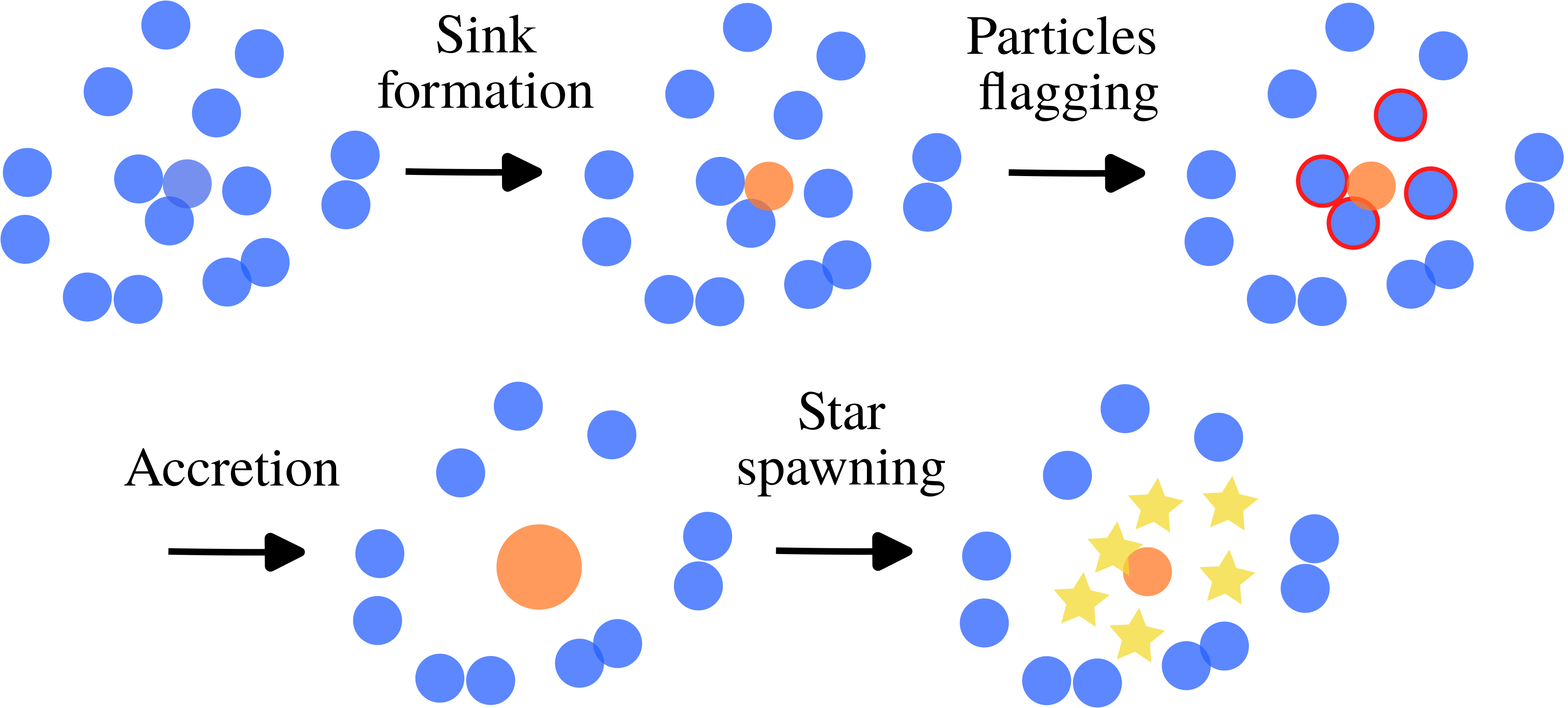

This figure illustrates the sink scheme. Eligible gas particles (blue) are converted to sink particles (orange). Then, the sink searches for eligible gas/sink particles (red edges) to swallow and finally accretes them. The final step is to spawn star particles (yellow) by sampling an IMF. These stars represent a continuous portion of the IMF or an individual star (the figure does not distinguish the two types of stars).

Here, we provide a comprehensive summary of the model. Sink particles are an alternative to the current model of star formation that transforms gas particles into sink particles under some criteria explained below. Then, the sink can accrete gas and spawn stars. Sink particles are collisionless particles, i.e. they interact with other particles only through gravity. They can be seen as particles representing unresolved regions of collapse.

We sample an IMF to draw the stars’ mass and spawn them stochastically. Below, we provide a detailed explanation of the IMF sampling. In short, we split the IMF into two parts. In the lower part, star particles represent a continuous stellar population, similar to what is currently implemented in standard models. In the second upper part, star particles represent individual stars. Then, the feedback is improved to take into account both types of stars. Currently, only supernovae feedback is implemented. Thus, the sink particle method allows us to track the effects of individual stars’ supernovae in the simulation.

The current model includes sink formation, gas accretion, sink merging, IMF sampling, star spawning and finally supernovae feedback (type Ia and II). The figures below illustrates the scheme and the associated tasks.

Our main references are the following papers: Bate et al., Price et al. and Federrath et al.

Note

Sink examples are available in examples/SinkParticles/. They include self-gravity, cooling and feedback effects.

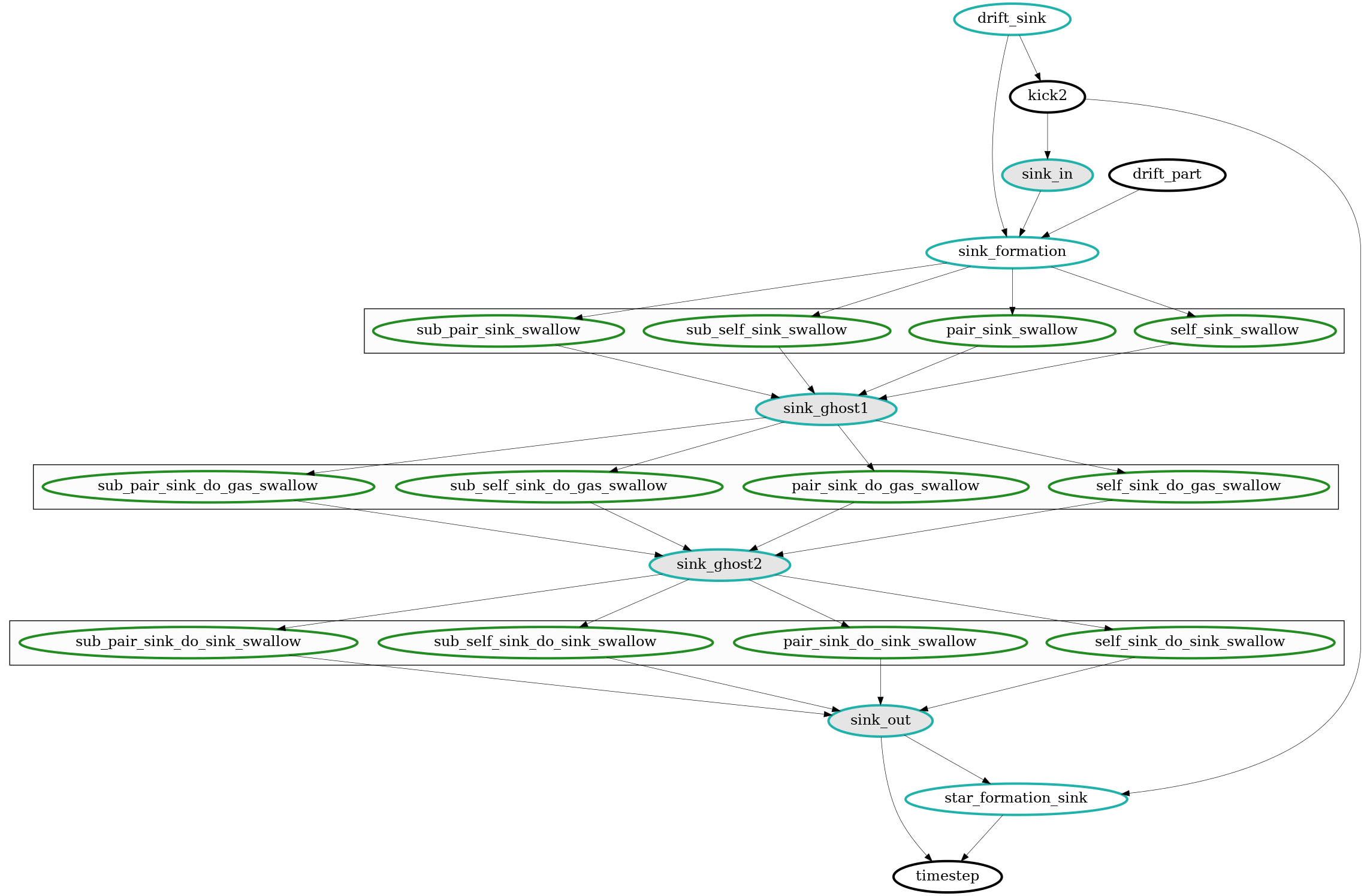

This figure shows the task dependencies for the sink scheme. The first rectangle groups the tasks that determine if sink particles will swallow other sink particles or gas particles. In the second one, the gas particles tagged as “to be swallowed” are effectively swallowed. In the third one, the sink particles tagged as “to be swallowed” are effectively swallowed. This was done with SWIFT v0.9.0.

Conversion from comoving to physical space

In the following, we always refer to physical quantities. In non-cosmological simulations, there is no ambiguity between comoving and physical quantities since the universe is not expanding, and thus, the scale factor is \(a(t)=1\). However, in cosmological simulation, we need to convert from comoving quantities to physical ones when needed, e.g. to compute energies. We denote physical quantities by the subscript p and comoving ones by c. Here is a recap:

\(\mathbf{x}_p = \mathbf{x}_c a\)

\(\mathbf{v}_p = \mathbf{v}_c/a + a H \mathbf{x}_c\)

\(\rho_p = \rho_c/a^3\)

\(\Phi_p = \Phi_c/a + c(a)\)

\(u_p = u_c/a^{3(\gamma -1)}\)

\(\nabla_p = \frac{1}{a} \nabla_c\)

Here, \(H\) is the Hubble constant at any redshift, \(c(a)\) is the potential normalization constant and \(\gamma\) the gas adiabatic index. Notice that the potential normalization constant has been chosen to be \(c(a) = 0\).

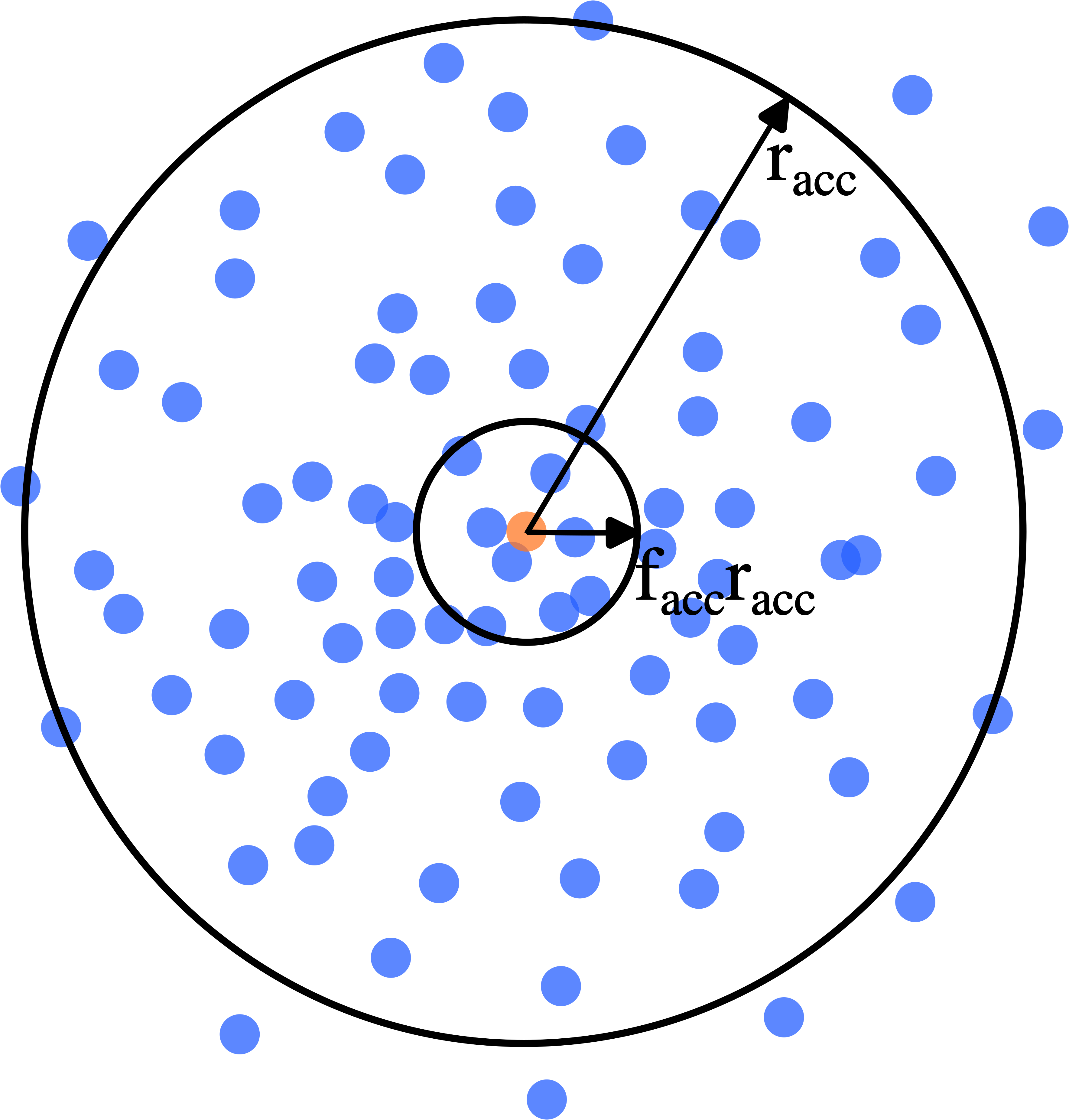

Sink formation

This figure shows a sink particle (in orange) newly formed among other gas particles (in blue). The accretion radius is \(r_{\text{acc}}\). It is the one used for sink formation. There is also an inner accretion radius \(f_{\text{acc}} r_{\text{acc}}\) (\(0 \leq f_{\text{acc}} \leq 1\)) that is used for gas swallowing. Particles within this inner radius are eaten without passing any other check, while particles between the two radii pass some check before being swallowed.

At the core of the sink particle method is the sink formation algorithm. This is critical to form sinks in regions adequate for star formation. Failing to can produce spurious sinks and stars, which is not desirable. However, there is no easy answer to the question. We chose to implement a simple and efficient algorithm. The primary criteria required to transform a gas particle into a sink are:

the density of a given particle \(i\) is exceeds a user-defined threshold density: \(\rho_i > \rho_{\text{threshold}}\) ;

if the particle’s density lies between the threshold density and a user-defined maximal density: \(\rho_{\text{threshold}} \leq \rho_i \leq \rho_{\text{maximal}}\), the particle’s temperature must also be below a user-defined threshold: \(T_i < T_{\text{threshold}}\);

if the particle’s density exceeds the maximal density: \(\rho_i > \rho_{\text{threshold}}\), no temperature check is performed.

The first criterion is common, but not the second one. We check the latter to ensure that sink particles, and thus stars, are not generated in hot regions. The third one ensures that if, for some reason, the cooling of the gas is not efficient, but the density gets very high, then we can form a sink. The parameters for those threshold quantities are respectively called density_threshold_Hpcm3, maximal_density_threshold_Hpcm3 and temperature_threshold_K.

Then, further criteria are checked. They are always checked for gas particles within the accretion radius \(r_{\text{acc}}\) (called the cut_off_radius in the parameter file) of a given gas particle \(i\). Such gas particles are called neighbours.

Note

Notice that in the current implementation, the accretion radius is kept fixed and the same for all sinks. However, for the sake of generality, the mathematical expressions are given as if the accretion radii could be different.

So, the other criteria are the following:

The gas particle is at a local potential minimum: \(\Phi_i = \min_j \Phi_j\).

Gas surrounding the particle is at rest or collapsing: \(\nabla \cdot \mathbf{v}_{i, p} \leq 0\). (Optional)

The smoothing kernel’s edge of the particle is less than the accretion radius: \(\gamma_k h_i < r_{\text{acc}}\), where \(\gamma_k\) is kernel dependent. (Optional)

All neighbours are currently active.

The thermal energy of the neighbours satisfies: \(E_{\text{therm}} < |E_{\text{pot}}|/2\). (Optional, together with criterion 8.)

The sum of thermal energy and rotational energy satisfies: \(E_{\text{therm}} + E_{\text{rot}} < | E_{\text{pot}}|\). (Optional, together with criterion 7.)

The total energy of the neighbours is negative, i.e. the clump is bound to the sink: \(E_{\text{tot}} < 0\). (Optional)

Forming a sink here will not overlap an existing sink \(s\): \(\left| \mathbf{x}_i - \mathbf{x}_s \right| > r_{\text{acc}, i} + r_{\text{acc}, s}\). (Optional)

Some criteria are optional and can be deactivated. By default, they are all enabled. The different energies are computed as follows:

\(E_{\text{therm}} = \displaystyle \sum_j m_j u_{j, p}\)

\(E_{\text{kin}} = \displaystyle \frac{1}{2} \sum_j m_j (\mathbf{v}_{i, p} - \mathbf{v}_{j, p})^2\)

\(E_{\text{pot}} = \displaystyle \frac{G_N}{2} \sum_j m_i m_j \Phi_{j, p}\)

\(E_{\text{rot}} = \displaystyle \sqrt{E_{\text{rot}, x}^2 + E_{\text{rot}, y}^2 + E_{\text{rot}, z}^2}\)

\(E_{\text{rot}, x} = \displaystyle \frac{1}{2} \sum_j m_j \frac{L_{ij, x}^2}{\sqrt{(y_{i, p} - y_{j, p})^2 + (z_{i,p} - z_{j, p})^2}}\)

\(E_{\text{rot}, y} = \displaystyle \frac{1}{2} \sum_j m_j \frac{L_{ij, y}^2}{\sqrt{(x_{i,p} - x_{j,p})^2 + (z_{i,p} - z_{j,p})^2}}\)

\(E_{\text{rot}, z} = \displaystyle \frac{1}{2} \sum_j m_j \frac{L_{ij, z}^2}{\sqrt{(x_{i, p} - x_{j, p})^2 + (y_{i,p} - y_{j,p})^2}}\)

The (physical) specific angular momentum: \(\mathbf{L}_{ij} = ( \mathbf{x}_{i, p} - \mathbf{x}_{j, p}) \times ( \mathbf{v}_{i, p} - \mathbf{x}_{j, p})\)

\(E_{\text{mag}} = \displaystyle \sum_j E_{\text{mag}, j}\)

\(E_{\text{tot}} = E_{\text{kin}} + E_{\text{pot}} + E_{\text{therm}} + E_{\text{mag}}\)

Note

Currently, magnetic energy is not included in the total energy, since the MHD scheme is in progress. However, the necessary modifications have already been taken care of.

The \(p\) subscript is to recall that we are using physical quantities to compute energies.

Here, the potential is retrieved from the gravity solver.

Note

Currently, only the following hydro schemes are compatible: SPHENIX, Gadget2, minimal SPH, Gasoline-2, Pressure-Energy, GIZMO MFV and GIZMO MFM. These schemes are also the ones compatible with GEAR star formation scheme. Implementing the other hydro schemes is not complicated but requires some careful thinking about the cosmological terms in the definition of the velocity divergence (comoving vs non comoving coordinates and if the Hubble flow is included or not).

Some comments about the criteria:

The third criterion is mainly here to prevent two sink particles from forming at a distance smaller than the sink accretion radius. Since we allow sinks to merge, such a situation raises the question of which sink should swallow the other. This can depend on the order of the tasks, which is not a desirable property. As a result, this criterion is enforced.

The tenth criterion prevents the formation of spurious sinks. Experiences have shown that removing gas within the accretion radius biases the hydro density estimates: the gas feels a force toward the sink. At some point, there is an equilibrium and gas particles accumulate at the edge of the accretion radius, which can then spawn sink particles that do not fall onto the primary sink and never merge. Moreover, the physical reason behind this criterion is that a sink represents a region of collapse. As a result, there is no need to have many sinks occupying the same space volume. They would compete for gas accretion without necessarily merging. This criterion is particularly meaningful in cosmological simulations to ensure proper sampling of the IMF. This criterion can be disabled.

Once a sink is formed, we record it birth time (or scale factor in cosmological runs). This information is used to put the sink into three categories: young, old and dead. If a sink is dead, it cannot accrete gas or sink anymore. However, a dead sink can still be swallowed by a young/old sink. Young and old sink only differ by their maximal allowed timestep. Details are provided in Sink timesteps.

Note

However, notice that contrary to Bate et al., no boundary conditions for sink particles are introduced in the hydrodynamics calculations.

Note

Note that sink formation can be disabled. It can be useful, for example if you already have sinks in your initial conditions.

Gas accretion

Now that sink particles can populate the simulation, they need to swallow gas particles. To be accreted, gas particles need to pass a series of criteria. In the following, \(s\) denotes a sink particle and \(i\) is a gas particle. The criteria are the following:

The sink is not dead. If it is dead, it does not accrete gas. A sink is considered dead if it is older than

timestep_age_threshold_unlimited_Myr.If the gas falls within \(f_{\text{acc}} r_{\text{acc}}\) (\(0 \leq f_{\text{acc}} \leq 1\)), the gas is accreted without further check.

In the region \(f_{\text{acc}} r_{\text{acc}} \leq |\mathbf{x}_i| \leq r_{\text{acc}}\), then, we check:

The specific angular momentum is smaller than the one of a Keplerian orbit at \(r_{\text{acc}}\): \(|\mathbf{L}_{si}| \leq |\mathbf{L}_{\text{Kepler}}|\).

The gas is gravitationally bound to the sink particle: \(E_{\text{tot}} < 0\).

The gas size is smaller or equal to the sink size: \(\gamma_k h_i \leq r_{\text{acc}}\).

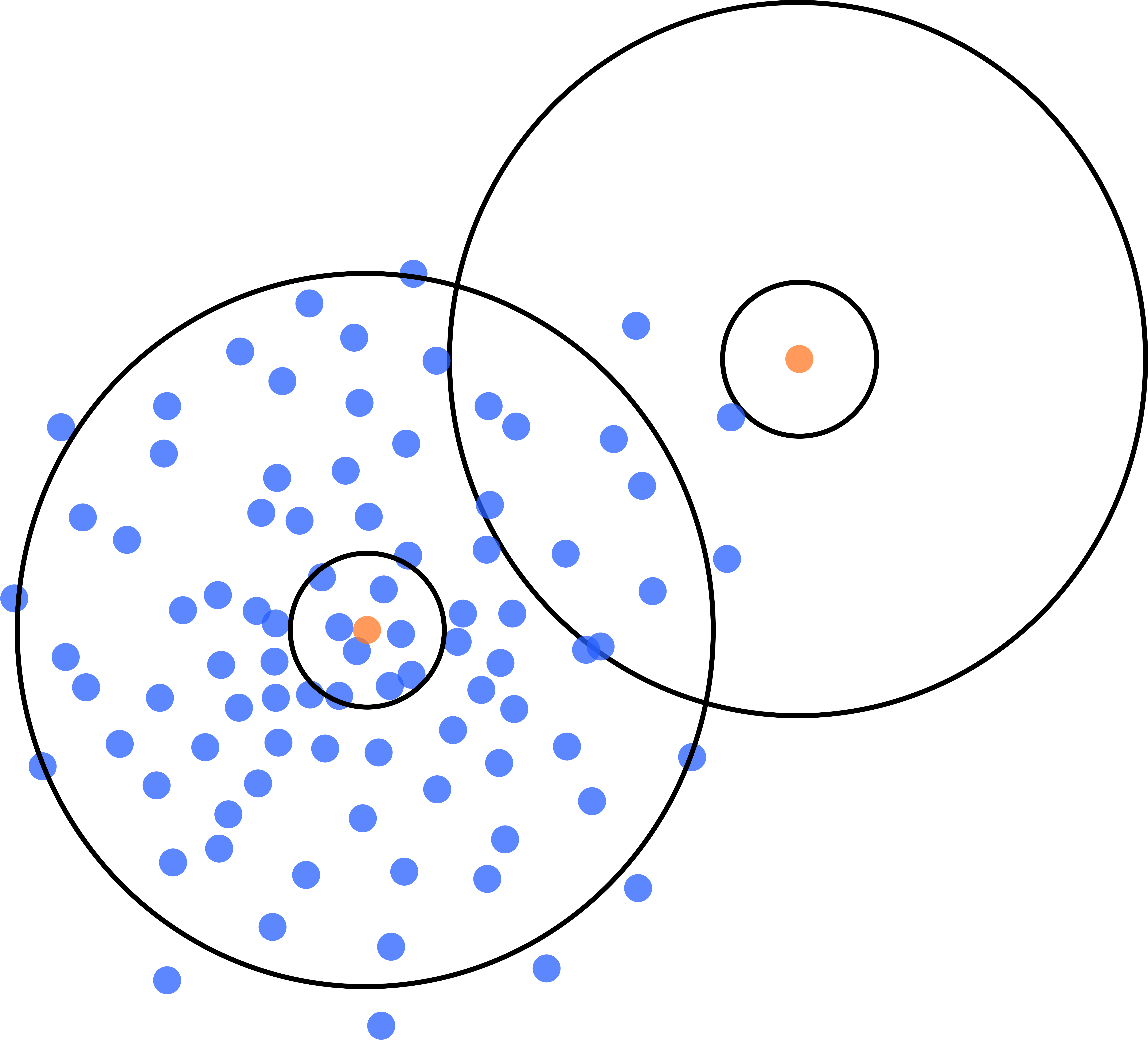

Out of all pairs of sink-gas, the gas is the most bound to this one. This case is illustrated in the figure below.

The total swallowed mass does not exceed

n_IMFtimes the IMF mass (see the IMF sampling section), but make sure to swallow at least one particle: \(M_\text{swallowed} \leq n_\text{IMF} M_\text{IMF} \text{ or } M_\text{swallowed} = 0\).

The physical specific angular momenta and the total energy are given by:

\(\mathbf{L}_{si} = ( \mathbf{x}_{s, p} - \mathbf{x}_{i, p}) \times ( \mathbf{v}_{s, p} - \mathbf{x}_{i, p})\),

\(|\mathbf{L}_{\text{Kepler}}| = r_{\text{acc}, p} \cdot \sqrt{G_N m_s / |\mathbf{x}_{s, p} - \mathbf{x}_{i, p}|^3}\).

\(E_{\text{tot}} = \frac{1}{2} (\mathbf{v}_{s, p} - \mathbf{x}_{i, p})^2 - G_N \Phi(|\mathbf{x}_{s, p} - \mathbf{x}_{i, p}|) + m_i u_{i, p}\).

Note

Here the potential is the softened potential of Swift.

Those criteria are similar to Price et al. and Grudic et al. (2021), with the addition of the internal energy. This term ensures that the gas is cold enough to be accreted. Its main purpose is to avoid gas accretion and star spawning in hot regions far from sink/star-forming regions, which can happen, e.g., if a sink leaves a galaxy.

Let’s comment on the fourth criterion, specific to our star formation scheme. This criterion restricts the swallowed mass to avoid spawning too many stars in a single time step. Swallowing too many gas particles in a time-step can lead to instabilities in the hydrodynamics, given that gas particles act as interpolation points. Also, creating many stars at once is prejudicial for two reasons. First, the stars’ mass samples an IMF, but the star’s metallicities do not. So, all stars end up with the same metal content. This situation does not reflect the history of metal accretion and will lead to poor galaxy properties. Second, we need to specify at runtime the maximal number of memory allocated for extra stars until the next tree rebuild. If we create more stars than this limit, the code will stop and send an error.

Since our politics is not to arbitrarily restrict the accretion using some arbitrary mass accretion rate (in fact, the accretion must be feedback-regulated), we then lower the sink time step to swallow the remaining gas particles soon. So, instead of eating a considerable amount of mass and spawning many stars in a big time step, we swallow smaller amounts of gas/sink and create fewer stars in smaller time steps. Details about the how we reduce the timestep are given in Sink timesteps.

Once a gas is eligible for accretion, its properties are assigned to the sink. The sink accretes the entire gas particle mass and its properties are updated in the following way:

\(\displaystyle \mathbf{v}_{s, c} = \frac{m_s \mathbf{v}_{s, c} + m_i \mathbf{v}_{i, c}}{m_s + m_i}\),

Swallowed physical angular momentum: \(\mathbf{L}_{\text{acc}} = \mathbf{L}_{\text{acc}} + m_i( \mathbf{x}_{s, p} - \mathbf{x}_{i, p}) \times ( \mathbf{v}_{s, p} - \mathbf{x}_{i, p})\),

\(X_{Z, s} = \dfrac{X_{Z,i} m_i + X_{Z,s} m_s}{m_s + m_i}\), the metal mass fraction for each element,

\(m_s = m_s + m_i\).

This figure shows two sink particles (in orange) with gas particles (in blue) falling in the accretion radii of both sinks. In such cases, the gas particles in the overlapping regions are swallowed by the sink they are the most bound to.

Sink merging

Sinks are allowed to merge if they enter one’s accretion radius. We merge two sink particles if they respect a set of criteria. The criteria are similar to the gas particles, namely:

At least one of the sinks is not dead. A sink is considered dead if it is older than

timestep_age_threshold_unlimited_Myr.If one of the sinks falls within the other’s inner accretion radius, \(f_{\text{acc}} r_{\text{acc}}\) (\(0 \leq f_{\text{acc}} \leq 1\)), the sinks are merged without further check.

In the region \(f_{\text{acc}} r_{\text{acc}} \leq |\mathbf{x}_i| \leq r_{\text{acc}}\), then, we check:

The specific angular momentum is smaller than the one of a Keplerian orbit at \(r_{\text{acc}}\): \(|\mathbf{L}_{ss'}| \leq |\mathbf{L}_{\text{Kepler}}|\).

One sink is gravitationally bound to the other: \(E_{\text{mec}, ss'} < 0\) or \(E_{\text{mec}, s's} < 0\).

The total swallowed mass does not exceed

n_IMFtimes the IMF mass (see the IMF sampling section), but make sure to swallow at least one particle: \(M_\text{swallowed} \leq n_\text{IMF} M_\text{IMF} \text{ or } M_\text{swallowed} = 0\).

We compute the angular momenta and total energies in the same manner as gas particles, with the difference that we do not use internal energy. Notice that we have two energies: each sink has a different potential energy since their mass can differ.

When sinks merge, the sink with the smallest mass merges with the sink with the largest. If the two sinks have the same mass, we check the sink ID number and add the smallest ID to the biggest one.

IMF sampling

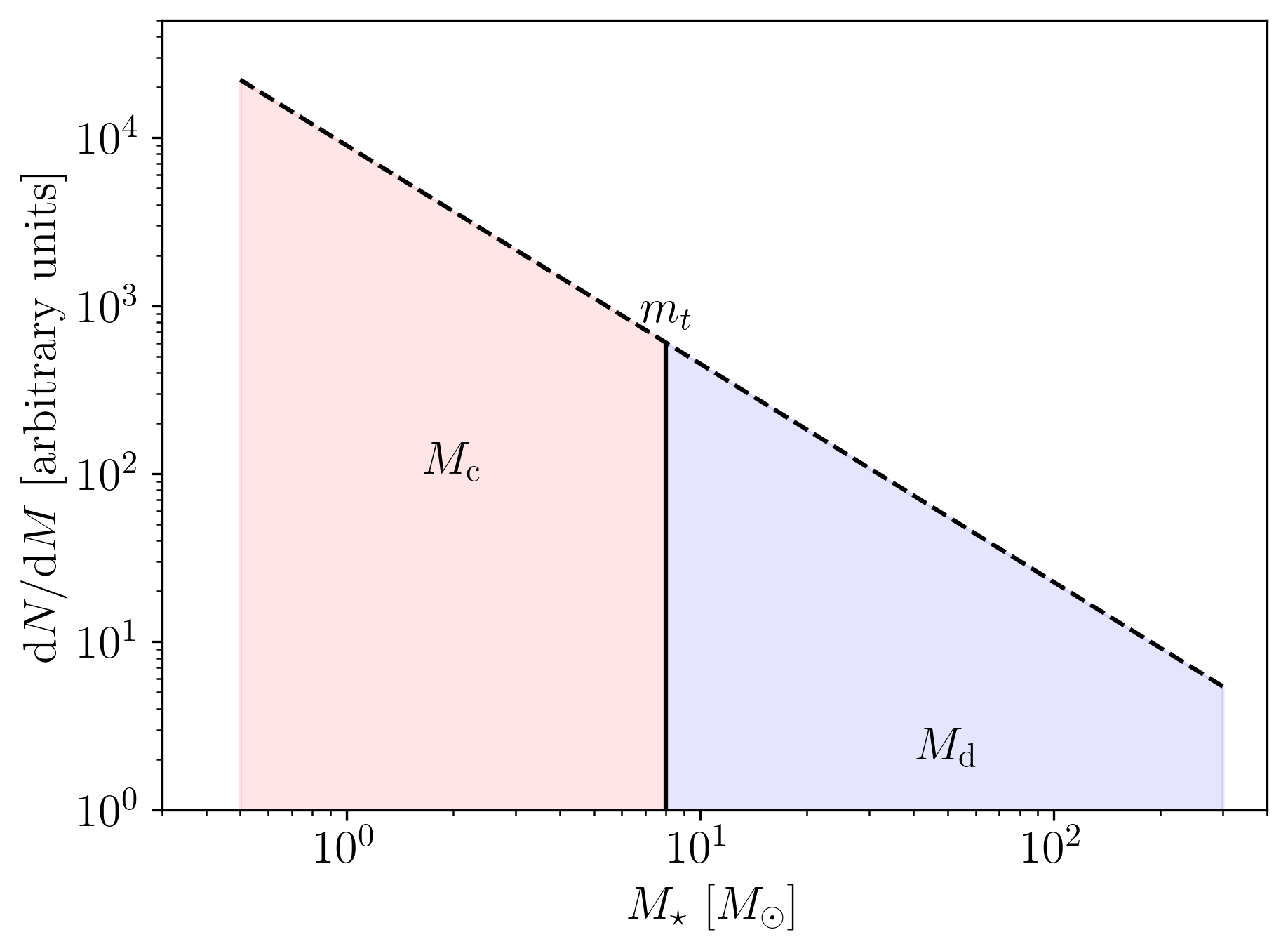

This figure shows an IMF split into two parts by \(m_t\): the continuous (orange) and the discrete (blue) part. The IMF mass is \(M_\text{IMF} = M_c + M_d\).

Now remains one critical question: how are stars formed in this scheme? Simply, by sampling an IMF. In our scheme, population III stars and population II have two different IMFs. For the sake of simplicity, in the following presentation, we consider only the case of population II stars. However, this can be easily generalized to population III.

Consider an IMF such as the one above. We split it into two parts at minimal_discrete_mass_Msun (called \(m_t\) on the illustration). The reason behind this is that we want to spawn star particles that represent individual (massive) stars, i.e. they are “discrete”. However, for computational reasons, we cannot afford to spawn every star of the IMF as a single particle. Since the IMF is dominated by low-mass stars (< 8 \(M_\odot\) and even smaller) that do not end up in supernovae, we would have lots of “passive” stars.

Note

Recall that currently (July 2024), GEAR only implements SNIa and SNII as stellar feedback. Stars that do not undergo supernovae phases are “passive” in the current implementation.

As a result, we group all those low-mass stars in one stellar particle of mass stellar_particle_mass_Msun. Such star particles are called “continuous”, contrary to the “discrete” individual stars. With all that information, we can compute the number of stars in the continuous part of the IMF (called \(N_c\)) and in the discrete part (called \(N_d\)). Finally, we can compute the probabilities of each part, respectively called \(P_c\) and \(P_d\). Notice that the mathematical derivation is given in the theory latex files.

Thus, the algorithm to sample the IMF and determine the sink’s target_mass is the following :

draw a random number \(\chi\) from a uniform distribution in the interval \((0 , \; 1 ]\);

if \(\chi < P_c\):

sink.target_mass = stellar_particle_mass;else:

sink_target_mass = sample_IMF_high().

We have assumed that we have a function sample_IMF_high() that correctly samples the IMF in the discrete part.

Now, what happens to the sink? After a sink forms, we give it a target mass with the abovementioned algorithm. The sink then swallows gas particles (see the task graph at the top of the page) and spawns stars. While the sink possesses enough mass, we can continue to choose a new target mass. When the sink does have enough mass, the algorithm stops for this timestep. The next timestep, the sink may accrete gas and spawn stars again. The sink cannot spawn stars if it never reaches the target mass. In practice, sink particles could accumulate enough pass to spawn individual (Pop III) stars with masses 240 \(M_\odot\) and more!

For low-resolution simulations (\(m_\text{gas} > 100 \; M_\odot\)), we also add a minimal sink mass constraint: the sink can spawn a star if m_sink > target_mass and m_sink - target_mass >= minimal_mass. In low-resolution simulation, when a gas particle turns into a sink, the latter can have enough mass to spawn stars, depending on the sink stars and IMF parameters. As a result, the sink spawns the stars and then ends up with \(m_\text{sink} \ll m_\text{gas}\). Such a situation is detrimental for two reasons: 1) the sink mass is so low that gas can seldom be bound to it and thus stops spawning stars and 2) the sink can get kicked away by gravitational interactions due to the high mass difference. The parameter controlling the sink’s minimal mass is GEARSink:sink_minimal_mass_Msun.

As explained at the beginning of this section, GEAR uses two IMFs for the population of II and III stars. The latter are called the first stars in the code. How does a sink decide which IMF to draw the target mass from? We define a threshold metallicity, GEARFeedback:imf_transition_metallicity that determines the first stars’ maximal metallicity. When the sink particle’s metallicity exceeds this threshold, it uses the population II IMF, defined in GEARFeedback:yields_table.

Star spawning

Once the sink spawns a star particle, we need to give properties to the star. From the sink, the star inherits the chemistry properties. The star is placed randomly within the sink’s accretion radius. We draw the star’s velocity components from a Gaussian distribution with mean \(\mu = 0\) and standard deviation \(\sigma\) determined as follows:

where \(G_N\) is Newton’s gravitational constant, math:M_s is the sink’s mass before starting to spawn stars, and \(f\) is a user-defined scaling factor. The latter corresponds to the star_spawning_sigma_factor parameter.

Stellar feedback

Stellar feedback per se is not in the sink module but in the feedback one. However, if one uses sink particles with individual stars, the feedback implementation must be adapted. Here is a recap of the GEAR feedback with sink particles.

All details and explanations about GEAR stellar feedback are provided in the GEAR Stellar evolution and feedback section. Here, we only provide the changes from the previous model.

In the previous model, star particles represented a population of stars with a defined IMF. Now, we have two kinds of star particles: particles representing a continuous portion of the IMF (see the image above) and particles representing a single (discrete) star. This new model requires updating the feedback model so that stars eligible for SN feedback can realise this feedback.

Discrete star particles: Since we now have individual star particles, we can easily track SNII feedback for stars with a mass larger than 8 \(M_\odot\). When a star’s age reaches its lifetime, it undergoes SNII feedback.

Continuous star particles: In this case, we implemented SNII and SNIa as in the previous model. At each timestep, we determine the number of SN explosions occurring. In practice, this means that we can set the minimal_discrete_masss to any value, and the code takes care of the rest.